Jaclyn’s story about a mother and son in her own words – Applying the therapeutic alliance to any relationship; What is ‘young’ anyway?

In SAVVY, SKILLS, SHARING STORIES & SOLUTIONS, I depart a little from our usual format to let you enjoy and learn from a mother’s story about how she applied the principles and practices of the therapeutic alliance to restore her relationship with her son. Not only did it rebuild the relationship but it empowered Leo to reach his full potential.

In SOUL, I am choosing to focus more on the joy of living than on my biological age. Even though I hit 73 this month, I don’t feel anywhere near that. How about you?

SAVVY, SKILLS, SHARING STORIES & SOLUTIONS

Last month, I presented at the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP) Annual Training Conference in Nashville, Tennessee. It was their largest conference ever with over 8,000 in attendance. I find it an important and informative conference for “anyone working at the intersection of addiction, mental health, and justice reform.”

As you can imagine, finding a seat in the large plenary sessions can be a challenge. As I scanned the available seats, I asked a young woman if that seat was open. She gestured for me to sit and leaned over to tell me she ‘met’ me on a video training she had recently reviewed. That was a happy coincidence to be acknowledged. But what was more gratifying was that she said that the training I had done on the therapeutic alliance particularly helped her improve her relationship with her 18 year old, senior high school son.

I’ll let Jaclyn tell her story about her relationship with her son, Leo (not their real names).

He Didn’t Choose this Life. He Wasn’t Sure He Wanted to Live it at All Anymore.

I could hear my son Leo sobbing in his room down the hall. My heart sank. Things had been going pretty well since his last melt down, I thought. His psychiatrist had him trying a different medication that wasn’t horrible. He’d started a different job at a local restaurant where he’d earn tips and get to work with a couple friends. He was finally out of the big box store he’d been earning minimum wage all throughout the pandemic, where people threatened him for enforcing masking rules and threw toilet paper at him over toilet paper purchasing limits. His grades were in the gutter, but I had hoped that somehow the new medication and the new job would be a kind of panacea that would turn the tide; that he’d magically start feeling great and somehow salvage his senior year.

Leo’s sobbing grew louder. I got up from the couch and tip-toed down the hall to knock softly on my son’s door. “Buddy, can I come in?” I asked quietly. I didn’t know what I would say or do if he said yes. We had always been really close, but it felt like our communication had been suffering more and more lately. He’d been floundering in his online classes, that were a forced result of the global shut-down. He was careening up and down emotionally, on the roller coaster of mis-diagnosed mental illness and the ensuing menagerie of ill-fitting medications.

Watching someone you love suffer is agony. The more I watched Leo suffer, the more I desperately tried to “help” in any way I could think of. Unfortunately, my “help” often showed up in the form of giving unsolicited advice, making suggestions, talking about how I would do things if I were him, and offering solutions. When none of that worked, I tried incentivizing. I tried sanctioning. I tried ordering…I tried to act like a confident leader; like I knew what I was doing. But the truth was I felt worried, afraid, inept, helpless, confused, alone, and sad. What had happened to the bright, social, confident son I used to know?

One thing was certain. My ineffective communication had been seriously eroding our relationship. Like many parents, I’d been holding on to what I thought he should be doing with his life. In doing so, I had managed to reduce our conversations to me trying to get him to come around by any tactic necessary, and him doing whatever he had to do to defend himself or avoid me. Our once strong relationship had come to feel superficial and transactional. I knew I didn’t want to keep communicating this way, but I also didn’t know how to fix it.

“You can come in,” he said, after taking a moment to collect himself. I took a deep breath and went in. I sat gingerly at the foot of his bed. I grabbed the box of tissues off the floor nearby and offered it to him. As he took it, I asked gently, “What’s going on?” As the tears welled up in his eyes again, he began to pour his heart out. Maybe it was because I was feeling so raw and powerless that I was actually able to just sit there and really listen to him that night, without trying to “fix” things. Maybe it was because what he said was the scariest thing a parent could ever hear come out of their child’s mouth. He said he didn’t want to live like this. He couldn’t see a future for himself. He didn’t choose this life. He wasn’t sure he wanted to live it at all anymore.

What do you say to that? Choking on my own tears, at some point I think I was able to eek out, “I’m here for you.” “I know you can make it through this.” and “I love you.” I sat there with him for a long time, just listening to whatever came out of him until his tears had passed, and he seemed temporarily relieved. I was not relieved. I lay awake well into the night, staring at the ceiling, tears streaming down my cheeks, wishing I knew how to support him.

At Work

I felt like a zombie at work the next morning. I work in treatment courts and my task for the day was to review a handful of recorded trainings we needed to get uploaded into our learning management system to share with our staff. I chose the first video to watch because I really resonated with the title. It was Dr. David Mee-Lee’s “Doing Time or Doing Change?”

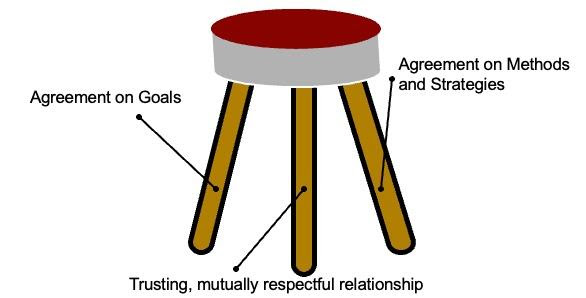

I had never been exposed to Dr. Mee-Lee’s work before, but my interest was piqued as he started discussing the importance of the therapeutic alliance and the three-legged stool that supports it. He described how alignment between treatment provider and participant in each of the three areas, or “legs”, (relationship, goals, and strategies) were critical. An example Dr. Mee-Lee used to illustrate this was how often we set ourselves up for failure when a participant starts a treatment court program, because we think the goal is abstinence from substance use, when the participant’s goal at that moment is actually to get everyone off their back, stay out of prison, and/or get their kids back. He talked about the importance of meeting the participant where they’re at, understanding what their proximal goals are, and working to support them in achieving those goals; engaging them while giving them agency over their life and treatment plan, leaving distal goals distal for now. As I listened, a lightbulb went off in my head.

The Lightbulb

I paused the video and considered my deteriorating relationship and communication with my son through the lens of these concepts. Were my son and I aligned on his goals? Absolutely not. My goal was for him to graduate high school, go to college, get a Ph. D., live a happy life, and eat his vegetables. His goal was to literally survive the mental health hell he was living through each day. Did we have alignment on strategies? Well, I had still been thinking that he should be able to somehow summon the will to get out of bed and take care of his school obligations in spite of his mental illness, so…we’ll call that a “no”. Were we aligned in our relationship? Definitely not. Our communication had more and more become me death-gripping outcomes and him resisting, retreating, and trying to protect the tiny shred of self-confidence he had left. Our therapeutic alliance didn’t have a leg to stand on. No wonder we were struggling.

I’m not a therapist. My son is not my patient. I’m not a treatment court team. My son is not a participant. Still, I figured it couldn’t hurt to at least apply these concepts and try to work towards more alignment with my son in goals, strategies, and relationship. “What we’re doing certainly isn’t working, so what do I have to lose?” I thought.

I stopped hounding on Leo and stopped trying to motivate him via external mechanisms. I let go of my expectations and just focused on appreciating him, loving him unconditionally, listening, and enjoying our time together whenever possible. Gradually, we rebuilt trust and safety in our communication. With the relationship leg of our stool getting sturdier and my goals in the backseat, I was able to ask him, “What do you really want right now?” even though I was terrified of what the answer might be.

“I want to take my GED (General Education Diploma), move out, and get on with my life.” he told me. I resisted the urge to immediately react, even as I noticed my conditioned beliefs about “drop-outs” try to take over. I took a few deep breaths and engaged him in a discussion about why that felt right to him right now, why that was important, and what his plans were. He said he wanted to work more, save money, focus on art, and move into a condo with his friend, which was a dirt-cheap rent deal he didn’t want to pass up. He said if there was ever a time someone could get away with bailing on high school and getting a GED instead, this pandemic was the time. Future employers and potential college admissions staff would surely understand. I left my commentary, suggestions, and opinions out of the conversation. It wouldn’t have been my first choice, but he was eighteen, legally an adult, and he did have a decent point. I gave him my blessing and support.

He also told me he wanted to get screened for ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), because he felt like his psychiatrist wasn’t listening to him. She wasn’t understanding that his anxiety and depression were coming from watching everyone else be able to do all the basic life things that he knew he was supposed to do and really wanted to do, but that he lacked the executive function to complete; like he was always straining to grasp something that was just out of reach. He asked if I would help him navigate the insurance and medical system to find another doctor and get a proper diagnosis. We had alignment on proximal goals and initial methods to try.

We interrupt this story for Jaclyn to share some important Tips she learned from her relationship with Leo. Stay tuned, Jaclyn tells the rest of the story.

As the weeks and months went by and I worked to maintain alignment in the three areas of the therapeutic alliance with my son, I learned many things about supporting someone through their change process that were applicable to my son’s and my relationship and also to our work with treatment court participants.

Tip 1

The relationship is primary to the therapeutic alliance.

Building rapport, trust, and common ground is not a “soft skill”. A person has to know you genuinely care about them, appreciate them, and accept them, before they will trust and respect you enough to give your words or approval any weight. Our systems condition us to hyper-focus on compliance, goals, strategies, and outcomes; incessantly keeping score. Paradoxically, putting relationships first almost always leads to better outcomes in less time along with an increased chance of sustained change.

Tip 2

People need agency and hope to take the first small steps that lead to lasting change.

Aligning with another in relationship, goals, and strategies and offering your genuine support shows that you trust that they innately know what’s best for themselves, which they ultimately do. As you demonstrate this confidence in them, they grow more confident in their own ability to make the right choices for themselves. Illustrating how you and others have made lasting change, despite challenges, and telling them how much you believe in them can give someone enough initial hope to give engagement in treatment a chance.

Tip 3

People change when they’re motivated to change.

Yes, anyone can be motivated to make short term change through coercion, but if the coercion persists it will ultimately breed resentment and damage the relationship. Long term change that leads to lasting recovery has to come from an individual’s own desire to feel good and have a better life. It is critical to learn what the person you’re working with wants and why they want it. Once you understand what truly motivates them, you can support them in moving towards it.

Tip 4

Small steps over time lead to big, sustainable change.

If you can support someone in getting to their first proximal goal, then their next proximal goal, and their next, eventually that distal goal, like sustained recovery, will be their next proximal goal. Starting with goals that feel unattainable from where the person we’re working with is a recipe for overwhelm induced self-sabotage. Instead, support them in taking one small, attainable step at a time and celebrate the small victories along the way.

Tip 5

Supporting sustained change is a dynamic scaffolding process in which we must continually meet the person where they’re at.

People don’t go from point A to point Z in one giant leap, or even in a straight line. When we expect someone to, we’re setting the stage for disappointment, discouragement, and perhaps giving up on the process. People learn their true strength by overcoming adversity, surviving, succeeding, and thriving, even if it’s a messy process. Supporting someone through this process is a privilege. Our work is to hold the faith and stay the course.

And now the rest of the story

Things didn’t change overnight in Leo’s life or in our relationship, but as I became a better listener and stepped back into a more comfortable and appropriate “consultant” role, things began to slowly and steadily improve. It takes time to build real trust.

We recently discussed our memories of how we each felt during that time. I remember feeling relief tip the scales to outweigh my fear, because I knew somewhere within that we were on the right path. He told me he remembers feeling things shift; that he could feel the difference between when I was scared for him and when I was trusting him to know what was best for him and how best to go about it. As he began to trust that I trusted him, his own confidence grew, and our relationship started to heal.

Two Hours of Sleep, a Red Bull, and a Cinnabon

He scheduled his GED tests and passed them all with college-ready scores in one morning, on two hours of sleep, a Red Bull, and a Cinnabon. Classic. I helped him navigate the insurance and medical systems until he found a new psychiatrist in our network who specialized in ADHD and got on their books. We took a “victory tour” road trip around the west coast and southwest US and had a blast together. He moved into his friend’s condo and took on more hours at his job.

He Didn’t Really Believe his Life Could Be and Stay Better

Due to the pandemic backlog, he had to wait a few months for his first appointment with his new doctor. There continued to be some scary times as he waited it out on the mental health roller-coaster. I’m proud of us for both holding the faith and staying the course. When he started his ADHD medication, there was an immediate and noticeable improvement, but I could tell he didn’t really believe his life could be and stay better. He told me he was still paranoid that things would somehow fall apart.

I Corralled my Over-Zealous Self

As the months went by, many other things started to go well for him. I remember him telling me excitedly one morning how nice it was to “be able to think a linear progression of thoughts,” something most of us take for granted. After a few more months he reported that he felt like the minimum-wage job path he was on felt like a “never-ending black hole” to him and that he was interested in going to college. I corralled my over-zealous self who formerly would have begun excitedly throwing options and ideas at him and simply let him know I was there for him as a sounding board as he explored the idea further. He has always loved plants and found a botany program at a nearby college he was interested in. I tempered myself even more. Instead of offering unsolicited advice and my own version of support, I just asked him, “If you wanted any support, what would support from me look like in this?”

He navigated the ropes of applying for the Botany undergraduate program mostly himself, and the times when he did ask for support in the process felt so much more natural when they came from his genuine desire for support in attaining his personally important goals. Just a few months into his program, he was thrilled about it and excelling in it.

Brimming with Excitement

I loved watching his confidence in trusting his own natural impulses grow as he continued to feel better and better and have more and more small wins. He started taking himself to a neighboring university’s well-renowned herbarium to use their preserved plant specimens as drawing references. One day, he came through the door just brimming with excitement. He announced that a professor at the university had taken an interest in his artwork and was going to contract him to do the botanical illustration for a plant species she’d recently discovered on another continent. It would to be published to science for the first time in a scientific journal and it would be his art. I’ll never forget the look in his eyes in that moment; when we both knew he’d turned the corner. It was the deep relief of someone who had fought a long, hard battle and won, and the confident self-efficacy of someone who also believed in himself enough to create a new joyful life.

He did an amazing job on the botanical illustration and his confidence and joy have only continued to grow. Our relationship is healthy and sincere. I love hearing him tell me about how he wants to continue on academically, maybe getting a master’s degree or going even further, because he’s passionate about research and conservation in the field. He continues to create and share beautiful artwork. He is taking excellent care of himself because he truly values himself. He is self-directed, self-disciplined, and intrinsically motivated. I’m happy for him and inspired by him.

What I Wish for You

This is what can happen for our relationships both personally and professionally if we are willing to trust that others innately know what’s best for themselves and if we’re willing to be a supportive component in their individual process. I have since applied these concepts generously to my life and work and have come to see that this kind of blossoming is the natural by-product of a healthy therapeutic alliance properly supported and balanced by the three “legs” of the stool (relationship, goals, strategies). I genuinely hope these principles I learned from Dr. Mee-Lee benefit you and yours as much and more.

Sincerely,

Jaclyn Prince

Thanks, Jaclyn for your inspiring story of hope if we embrace the principles and practices of the therapeutic alliance. If you would like to see a version of the video training that Jaclyn reviewed, you can sign in for free at TREATMENT COURTS ONLINE – The National Training System for Treatment Court Practitioners.

Instructions:

1. Go to https://treatmentcourts.org/

2. Create account and login

3. Select the “Adult Drug Courts” icon on the main page

4. Select the first item on the list “Adult Drug Courts: Lessons”

5. Select Lesson: “Doing Time or Doing Change?” The specific section on

“What Works in Treatment and the Therapeutic Alliance” starts at minute 5:16

soul

Jaclyn’s story flowed just as she had written it. I tweaked it only to add some headings to paragraphs to fit my Tips and Topics format. But I thought I had better run it by her before publishing in case she had any edits. Fortunately Jaclyn was delighted by what I had done with her piece and said she would “hold onto the reference to me as a ‘young woman’ for years to come ;)”

Like most of us in Western culture, I guess Jaclyn liked feeling and being seen as ‘young’. Since I just turned 73, she was certainly a young woman to me. However if you do the math, you can’t be a mother of an 18 year old and still be a young woman in her twenties (I did go to medical school).

But what is ‘young’ anyway? I feel like I am 53 or even 43. So far I have been blessed with good health and mobility and can still hold my own in an intelligent conversation ….no sign of drooling or blank, vacant stares so sad to see in some older adults.

I am choosing now to focus on the joy of living and will deal with any obstacles as they arise, paying as little attention to my biological age as possible. Just maybe those obstacles will be slow in coming.

Or as Jaclyn said “maybe 40s are the new 20s and maybe 70s are the new 40s.”